By Mike Frick

After a year of secretive negotiations and public pomp and drama, China unveiled its new leaders. But alongside the official narrative of this once-a-decade transition, Chinese grassroots organizations and individual citizens took part in their own smaller-scale dramas when they stood up, individually and collectively, to demand a more equal society. The year 2012 saw creative – sometimes daring – examples of advocacy in the field of health and human rights.

Here is a look-back at some notable campaigns led by activists who demanded equal rights for LGBT people, women, male and female sex workers, disabled people, and people living with hepatitis or HIV/AIDS.

Ending Discrimination Against People Living with HIV/AIDS

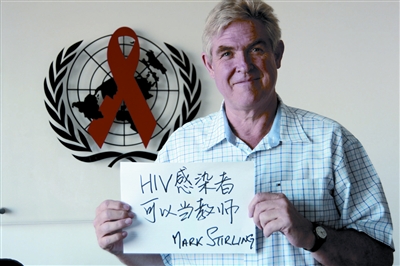

UNAIDS China Country Coordinator Mark Stirling in the “Ten Thousand Smiles” Campaign | Source: People’s Daily

Chinese public-interest organization Justice for All set the tone for the year on December 1, 2011, World AIDS Day, when they mailed 12,621 photos to the Chinese Human Resources and Social Insurance Departments. Each photo profiled a smiling person holding a hand-written sign with a slogan supporting equal rights for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). The campaign was picked up by local media, and then by the People’s Daily, the official organ of the Communist Party.

The “Ten Thousand Smiles Campaign” was the inspiration of Yu Fangqiang, founder and executive director of Justice for All. He began taking photos of people holding anti-discrimination signs at an HIV/AIDS advocacy workshop sponsored by UNAIDS, Asia Catalyst, Korekata AIDS Law Center and SECTION 27, a South African human rights group. Yu Fangqiang and his colleagues persuaded U.S. Ambassador Gary Locke, among others, to allow their photos to be used in the campaign. The campaign spread, and college students gathered thousands more photos, which they shared online. Premier Wen Jiabao subsequently called on government departments to eliminate discriminatory policies against PLWHA.

Later in the year, activists brought the movement to China’s most iconic cultural heritage site with the first China AIDS Walk on the Great Wall on October 13, 2012. Led by the Beijing Gender Health Education Institute (BGHEI), a member of Asia Catalyst’s 2012 Nonprofit Leadership Cohort program which provides year-long nonprofit management and advocacy training, the fundraising drive raised over 150,000 RMB for anti-discrimination programs across China. Half of the funds will help Tianjin Dark Blue Working Group, an NGO that serves men who have sex with men in Tianjin, off-set the costs of antiretroviral treatment among socially-disadvantaged members of their community.

Feminist Flash Mobs

Breast feeding flash mob in Wuhan City | Source: Danwei

“If you love her, do not make her wait,” read a sign held by a young woman blocking the entrance to a public men’s restroom in Guangzhou. In February 2012, men using a public bathroom at a Guangzhou park were surprised to find college student Li Maizi and other women “occupying” the men’s stalls to protest unequal wait times.

The toilet occupations soon spread to other Chinese cities, including Beijing and Nanjing, where women commandeered men’s rooms to highlight unfair national standards that set a 1:1 ratio for men’s and women’s restroom construction. Activists pointed to Hong Kong and Taiwan, where laws mandate a more equitable 1:1.5 ratio. The occupations prompted the Guangzhou City Government to commit to a 1:1.5 ratio for new toilet construction.

Restroom occupations in the winter gave way to bare heads in the summer as women in Guangzhou and Beijing shaved their heads to protest gender discrimination in university admissions. Holding signs reading “admissions equality”, four women with shaved heads in Guangzhou posed for photos to call attention to the Ministry of Education’s practice allowing universities to set lower admissions standards for men than for women. At Renmin University in Beijing, for example, men studying select foreign languages must score only 601 points on China’s national college entrance examination, compared to 614 points for women.

This streak of creative, body-driven advocacy continued when mothers in Wuhan and other cities formed breast-feeding flash mobs to protest China’s powerful infant formula industry and a medical system that pushes cesarean delivery over natural birth. Over 45% of Chinese mothers give birth by caesarean section, a higher percentage than in any other country, and new mothers often leave hospitals with care packages from corporate infant formula manufacturers.

Activists drew attention to these actions through a combination of media outreach and creative use of Weibo, Chinese social media.

Disabled Activists Demand a Barrier-Free Society

Blocked wheelchair entrance to Zhengzhou Railway Station | Source: Yirenping

People with disabilities also took to public spaces to demand a “barrier-free society,” working with Beijing Yirenping Center to document public actions and get the word out online.

On August 11, 2012, China’s National Day for People with Physical Disabilities, activists in Zhengzhou and other cities staged “performance art” events to highlight barriers to access. In Zhengzhou, three activists in wheelchairs conducted a “money, but no access” demonstration in which they gathered outside banks that lacked access ramps, unable to deposit their money or open accounts.

Across the city, Wang Jinlei drew attention to the locked wheelchair access point at the Zhengzhou Railway Station. Meanwhile, activists in Hefei and Nanjing wrote letters to their cities’ respective Transportation Bureaus to make recommendations for ways to improve access to bus and public transportation.

Activists also challenged barriers to equal education. Xuan Hai, a blind graduate of Anhui School of Finance, was twice turned away from taking the civil service exam due to the registrar’s failure to provide an accessible testing facility or tests in Braille. With help from Beijing Yirenping Center, Xuan Hai applied for and received an official “administrative reconsideration.” A number of disability rights activists also worked together to submit recommendations for China’s periodic review by the monitoring body for the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Campaigning for Sex Worker Rights

Sex worker activists also used a combination of one-day actions, social media and the press to spark a public discussion about the challenges they face. In January, sex worker advocate Ye Haiyan, who goes by the name Hooligan Swallow, spent two days working alongside sex workers in a “ten yuan” brothel that serves migrant workers. Ye Haiyan provided sexual services for free to draw attention to the high fines police levy against sex workers, and took photographs to document the harsh conditions in low-end brothels. She shared the photographs on Weibo, drawing attention from mainstream media and starting a lively discussion online about decriminalization. Ye Haiyan has been one of the most outspoken critics of China’s criminalization of sex work, which a 2011 report by the China Sex Worker Organization Network showed places sex workers at greater risk of acquiring HIV.

Chinese sex workers also took their voices to the XIX International AIDS Conference in Washington, D.C., where Asia Catalyst held a roundtable discussion with members of the China Sex Worker Organization Network and groups that do outreach to male and female sex workers in China. Due to the US travel ban on sex workers and drug users with criminal convictions, these advocates were among just a handful of sex worker representatives at the world’s largest conference on HIV/AIDS. Many sex workers and their allies, including Chinese activists, convened a satellite session in Kolkata, where they strategized, shared information and marched to demand human rights for sex workers.

Advocating for Rights of People with Hepatitis

Just before World Hepatitis Day on July 29, 2012, authorities blocked China’s most popular website for people living with hepatitis B (HBV). Since its creation in 2003, the website In the Hepatitis B Camp has provided a platform through which HBV activists have shared information, organized to sue companies for employment discrimination and fought back against schools for rejecting children with HBV. It has also frequently been blocked by authorities.

In response this time, Yirenping wrote: “We can’t help but ask, ‘Why do the authorities not allow the existence of a website which enables disadvantaged people to help one another?’ We can’t help but ask, ‘Is it wrong for millions of people living with HBV to demand anti-discrimination, equality and fundamental rights?'” Access to In the Hepatitis B Camp has since been restored.

HBV activists also advocated for the rights of their community on the ground. In Sichuan Province, Chengdu E Road Working Group, another member of Asia Catalyst’s Nonprofit Leadership Cohort, helped eight recent college graduates successfully win their jobs back from a military-backed company that fired them on the basis of their HBV status.

Cheng Zhuo, director of Chengdu E Road, taught these eight individuals how to collect evidence, negotiate with their employer and prepare for litigation. But again, it was the power of the media – including an article published by Xinhua – which drew public attention to their case and persuaded the company to rehire all eight individuals.

First National LGBT Conference

Aibai Transgender Program Manager Wu Jisuan at the LGBT Community Leader Conference | Source: Queer Comrades

It was a big year for BGHEI: In addition to holding the first China AIDS Walk, the group also convened the first national LGBT Community Leader Conference in June 2012.

The conference attracted over 100 delegates from fifty-three LGBT organizations. Discussions focused on LGBT movement-building and the challenges of building solidarity and collaboration across different constituencies. In opening the two-day event, BGHEI executive director Wei Jiangang pointed out the unprecedented diversity of voices in the room, including traditionally under-represented groups such as disabled persons, transgender persons, and male sex workers.

And as recently reported on the Asia Catalyst blog, Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG) China executive director A Qiang used his Weibo account to call attention to a statement by the China Center for Adoption Affairs prohibiting gays and lesbians from adopting children. In a message posted on its website, the agency claims that medicine considers homosexuality a type of illness, that Chinese law does not recognize homosexual families and that homosexuality is a behavior “contrary to public morality.”

In a separate action, PFLAG China helped parents in Hangzhou write a letter to the Hangzhou City Department of Education protesting a sex education booklet that labeled homosexuality an “acquired abnormal sexual behavior.”

Innovative Media Advocacy

Although the above actions spoke for distinct communities, several emerging trends unite grassroots Chinese advocacy. While many activists used traditional tools such as letter-writing and litigation, a growing number are using performance art (行为艺术) to take advocacy into the public realm without risking the type of full demonstrations that are restricted in China. Despite the small sizes of the toilet occupations, breast feeding flash mobs and other events, these actions generated widespread media coverage and were often picked up and repeated by people in other cities. These efforts were all the more remarkable for how they put human bodies front and center, from women shaving their heads outside universities to disabled persons confronting the many physical barriers to their participation in public life.

Social media also helped activists take their message to a wider audience. While sites like Weibo played an important role, tried-and-true offline, peer-to-peer influence underlay the success of the 10,000 Smiles Campaign and the China AIDS Walk, which picked up momentum when friends asked friends to participate.

In a challenging, unpredictable year, Chinese grassroots activists found innovative ways to bring the voices of their communities to a national – and sometimes international – stage. We look forward to seeing what these activists have in store for 2013.